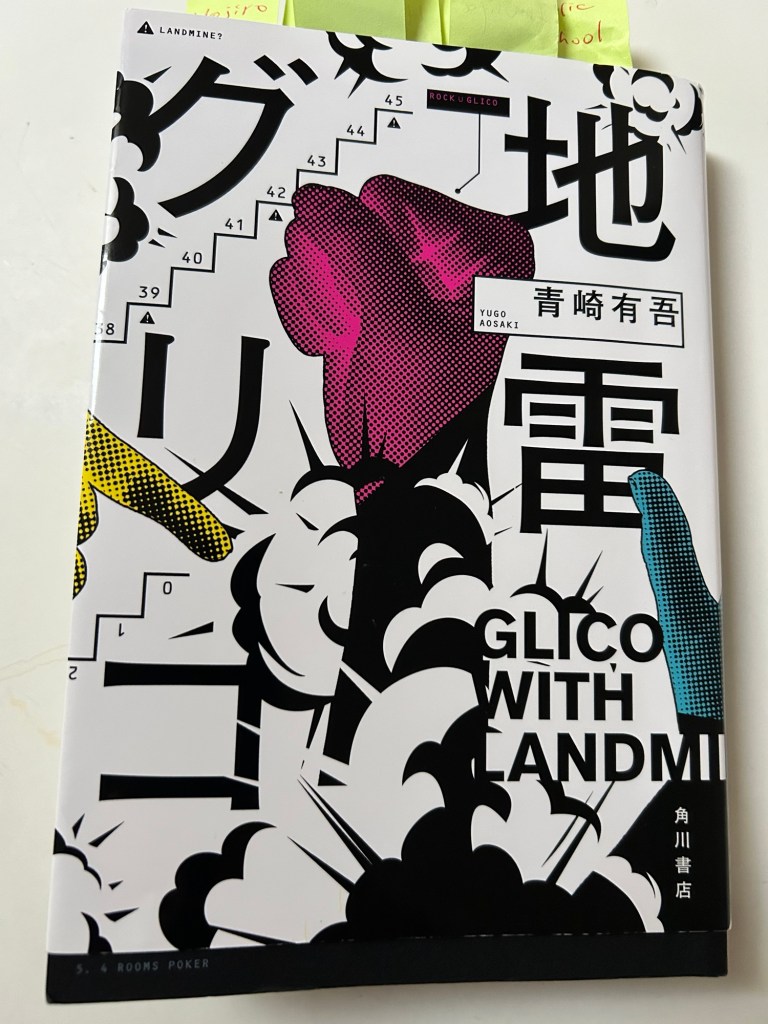

Earlier this year, I read about this book, “Glico with Landmines,” in an article in the major Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun. The story mentioned that this work, which is a fictional account of high school students playing variations of popular card games and playground games, had been awarded three literary prizes[1] in one week. A prize-winning book about games! Seems like a winning combination that’s worthy of attention.

The book is a collection of novellas with a consistent storyline that features the same core characters. The main characters are Mato Imoriya, who is in her freshman year of senior high school and her friend Koda, as well as Hayato Kunugi, a senior known for his gaming prowess, and Nuribe, a freshman game judge, who belying his geeky looks, plays lacrosse. They are all students at Hojiro Senior High School, a public school in Tokyo. The first story, which the book is named after, involves a contest between Imoriya and Kunugi. The two are representing their respective homeroom classes in a head-to-head competition, with the winner gaining the rights to use the rooftop during an annual student-run school festival. Imoriya’s class plans to open a curry shop at the festival and Kunugi’s class a cafe.

Rather than flip a coin or play a simple game of rock-paper-scissors, the two agree to duke it out in a game of “Glico with Landmines,” a game designated by Nuribe the judge, who is also a member of a school committee running the festival.

“Glico” is a playground game popular in Japan. The goal is to cross the finish line first. The finish line can be any agreed upon distance, but let’s say it’s 50 paces away and there are two players in the game. Each turn, they play rock-paper-scissors. If a player wins by putting out a rock, which is known as “guu,” they advance three steps for each syllable in the Japanese word “Glico,” which is the name of a popular candy manufacturer whose symbol—a male runner raising his arms in victory—adorns the side of a building in Dotonbori in Osaka[2], and which makes caramel candy[3] as one of its flagship products. If a player wins by putting out scissors, known as “choki,” they advance six steps for each syllable in the Japanese pronunciation of “chocolate.” Win by putting out paper, known as “paa,”and the player advances six steps for each syllable in the Japanese pronunciation of the word “pineapple.”

I don’t think I played this game much, if ever, but it seems to be popular now, and every so often you’ll come across kids and families playing the game at a local park. Is it perhaps seeing a surge in popularity because of this book?

In ”Glico with Landmines,” the objective is to reach the goal, which is 46 paces away. The playing field is a staircase that leads up to a shrine located near the students’ high school. Each player gets three “landmines,” which can be planted on any of the 45 spaces between the starting point and the goal. At the start of the game, each player writes the locations of their landmines on a piece of paper. Only one mine can be planted in a single space. If both players plant mines on the same square, the judge reveals the location, and tells the players to re-plant the mines. The other twist is that any time there are 5 consecutive ties in a match of rock-paper-scissors, the player closest to the goal, or if both players are on the same space, the player who arrived there first is considered to have won that match and can advance either three or six spaces at their discretion.

During the game, if a player stops on a space with a landmine planted by the opponent, the player takes a hit and must immediately go back 10 spaces. If a player stops on a space with their own landmine, that is considered a miss and while the player gets to stay on that space, the location of their landmine is revealed to the opponent.

Given such rules, where should players plant their landmines? The students watching the competition between Imoriya and Kunugi figure that the most effective locations would be any space that is 12th or higher and a multiple of three, given that players that win at rock-paper-scissors must always advance three or six spaces.

Kunugi takes the early lead and advances to square 39 without stepping on any mines, while Imoriya languishes at square 27, having landed on a couple of Kunugi’s mines and been forced to retreat.

At that point, Imoriya resorts to trash talking, calling attention to the fact that Kunugi hasn’t landed on any of her mines yet, and declares she will catch up to and pass Kunugi on the very next turn. Imoriya adds that she has placed landmines on squares 42 and 45. Those two are the multiples of three that are closest to the goal, square 46, and hence are two of the most logical places to plant landmines. Since Kunugi has advanced this far without setting off any, it seems plausible that Imoriya has planted mines on both those squares. Kunugi, who is on square 39, must land on either 42 or 45, since players can only advance three or six spaces.

Kunugi decides to call Imoriya’s bluff. What did she have to gain by telling Kunugi that she’d placed mines on both spaces? With her declaration, Kunugi deduces that Imoriya is trying to trick him into attempting to advance to square 45, given that retreating 10 spaces from 45 is preferable to retreating 10 spaces from 42. The catch, Kunugi thinks, is that there is no mine on square 42, and only on square 45.

He reckons that since Imoriya wants Kunugi to advance six spaces to 45, she wants him to win with paper or scissors at the next rock-paper-scissors duel, meaning she will use rock or paper to lose. Kunugi, though, wants to advance three spaces to 42, so he needs to win with a rock against Imoriya’s scissors. So, how to get Imoriya to use scissors?

Kunugi tries to get Imoriya fixated on the large, 12-space gap between their positions, hoping to goad her into prioritizing a win in the next rock-paper-scissors match and closing the gap. Kunugi chides his opponent, saying: “A comeback on the very next turn? Aren’t you getting carried away?” Assuming Imoriya takes the bait and tries to win the next rock-paper-scissors round, she will probably use scissors since that would be good for a win, or at worst a tie, against the paper or scissors that she should be expecting Kunugi to use, to advance six spaces to 45. Or so Kunugi thinks.

With all this scheming on both sides, it’s time for another rock-paper-scissors duel. Imoriya uses scissors, losing to Kunugi’s rock, setting him up to advance three squares to 42. “There is no mine on space 42. Isn’t that right, Imoriya,” Kunugi says as he ascends the stairs, savoring what to his eyes seems like a walk to inevitable victory.

To find out who won and how, read the book. It includes four other stories featuring games of increasing complexity and competitions against increasingly devious opponents. The eponymous story, “Glico with landmines,” is the most straightforward game of them all. In all five competitions, each player must think long and hard to figure out what their opponent is thinking, so they can counter their moves and manipulate the opponent into making the wrong moves. It’s exhilarating watching the protagonist, Imoriya, take advantage of the boundaries set by the rules, and better yet, find opportunity and freedom in areas left undefined by them and not governed by any.

An intriguing, charismatic member, the president of the Hojiro High School Student Council, Nieko Saburi, later joins the cast of characters. A female student in her senior year, Saburi seemingly flouts all the school rules, wearing an ear piercing on her left ear, a ball chain and cross that cling with her every step. Saburi has dyed her short hair partially blue, and wears slacks instead of the skirts that are the standard uniform for female students at the school. She ran for school president just so her peers would not complain about her attire, persuading, cajoling, and pressuring them—without breaking a sweat—into supporting her candidacy. A formidable political operator and a natural who harbors no qualms about leveraging power for her own personal gain, Saburi lords over Kunugi. Seeing how reverentially Kunugi treats Saburi even though she is loath to do any of the student council work and content to leave those tasks to others, Goda glimpses a bit of Kunugi’s future. Kunugi-san is going to have a tough time when he joins the workforce, she thinks.

The students’ backstories become more and more compelling, providing incentive for the reader to keep turning the page. Imoriya’s final opponent is Esora Ukida, a fellow high school freshman who went to the same junior high school as Imoriya and Goda. Imoriya has a serious axe to grind against Ukida, saying she needs to apologize for something she did in junior high school. Goda tries to get Imoriya to explain why she is so intent on getting Ukida to apologize, but Imoriya, stoically focused on beating Ukida, keeps that to herself.

The author, Yugo Aosaki, is a writer in his 30s with several mystery novels to his credit among other works, having made his debut as a writer in 2012 while in college. According to the Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun, he expressed surprise when “Glico with Landmines” won three literary awards, saying that it’s only a story about high school kids playing games. Despite the author’s protestations, it is perhaps fitting, however, that such a book is garnering attention in Japan now, given how prolific games are these days—especially trading card games—in a manner reminiscent of the ubiquity of the Dragon Quest games in the late 1980s and 1990s.

The game savant, Imoriya, however, is no fan of games—even though she constantly finds herself strategizing. To her friend, Goda, she expresses indignation at those who say life is just a game or compare going through key experiences in life to the act of playing a game. It’s a refrain one often hears in Japan. A cram school instructor, for example, might say that the experience of studying for and taking school entrance exams is like a game, so the key is to treat it as such and enjoy it. Imoriya disdains such comparisons. If you treat an entrance exam like a game and fail, that will set you back a year, if you treat child-rearing like a game that’s not something you can do over. Life isn’t a game, she says.

Before each head-to-head match, Imoriya feels as though she’s standing on a rooftop’s ledge, with only empty sky below her feet. Safety is almost within reach, if only she can leap over a gap that is just slightly wider, 15 centimeters or six inches wider, than the length of her stride. To dismiss this sensation as something unique to competitions is wrong, Imoriya thinks. Whether one notices it or not, that sensation is always there, lurking in the background.

At one point, Goda asks Imoriya, what do games mean to you? To which Imoriya replies, “I don’t know, because I hardly ever play games.”

Indeed, Imoriya comes across as a person who sees the potential for destiny-changing experiences everywhere and at any time, whether one is going through the mundanity of everyday life or engaging full-throttle in high stakes competition. Don’t treat such moments like games, but rather, accord them the gravity they deserve, she seems to be saying.

[1] Mystery Grand Prize, Mystery Writers of Japan Award, and the Yamamoto Shugoro Award for popular literature. The book is also one of the finalists for the 171st Naoki Award, one of the two most prestigious awards in Japan for works of fiction, with the winner due to be selected in July 2024. https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASS5K2RZPS5KUCVL01LM.html

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20240613/k10014479081000.html

[2] There is a picture of the “Dotonbori Glico Sign” on the official website of the company, Ezaki Glico Co., Ltd. https://www.glico.com/jp/health/contents/glicosign/

[3] Long ago, these used to be square-shaped caramels, but judging from the Ezaki Glico website, they’ve evolved in recent years. https://www.glico.com/jp/product/gum_candy/glico/

コメントを残す