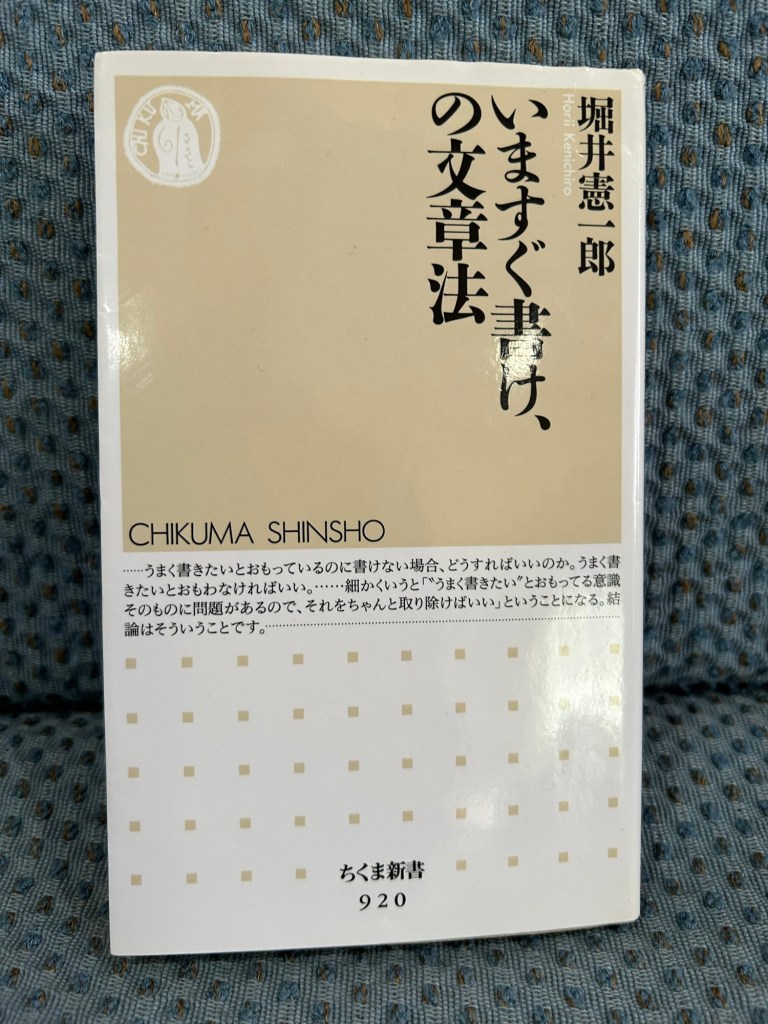

What is the difference between amateur writers and professional writers, asks Kenichiro Horii, in his 2011 book[1] “Imasugu Kake, no Bunshoho (The Write Now Writing Method).”

The difference is that amateurs write for themselves, while professionals write to satisfy their readers, says Horii, a veteran columnist and freelance writer who has written weekly columns for magazines in Japan. It’s not about how beautifully you can write, or how many words you know, but whether you are constantly thinking about providing a service to the reader and how you can keep them engaged, he adds.

START WRITING NOW

Horii, who has written dozens of books on topics ranging from youth culture, Disneyland, to Rakugo, a traditional Japanese form of comedic storytelling, urges those who have a desire to write to start immediately. Don’t wait until you’ve increased your vocabulary. Don’t wait until you’ve retired. Just start writing now, he says, adding that writing takes stamina so you’re better off writing now than putting it off until you’ve become older.

Earlier in his career, a magazine editor spotted Horii carrying a dictionary at work. So, you write with a dictionary, the editor said derisively. Horii later figured out why the editor had treated him with such scorn. He came to realize that trying to write using fancy words that you need to look up in a dictionary is folly, like going to battle with a high-tech weapon that you need an instruction manual for. You’d be much better off relying on your tried and tested wooden club and boomerang, Horii says.

FOCUS YOUR RESEARCH

The key to producing good magazine articles is to keep in mind that readers aren’t your friends. Most are strangers who don’t know anything about you and who don’t care who you are. They’re just flipping through the pages hoping to find something that captures their interest.

The aim should be to write something that changes the reader in some way. To do so, write about things that surprised you and tell the reader about it[2], Horii says.

To be sure, the writer needs to find interesting story ideas that make people curious to learn more. Such story angles might contain surprises, or something funny.

Writers can then pitch those angles to magazine editors. Once an idea is approved, writers can try to collect, through research and reporting, relevant data that supports their argument. With that data in hand, it’s up to the writers to tell an intriguing story.

Horii cautions against doing research for research’s sake. That never yields good results[3] and is a waste of time, he says. Research should always be done to prove a specific hypothesis, to support a specific point that you are trying to make[4]. That is the only useful way to do research, Horii says[5].

THE PHYSICAL NATURE OF WRITING

He stresses the importance of the following notion: “No one is all that interested in hearing someone else’s opinion. They just want to hear stories about other people[6].”

That statement sounds odd. Aren’t we often curious to know what other people think? Horii seems to be asserting that opinions and ideas that aren’t backed by hard-earned personal experiences, will lack punch and persuasiveness.

Write about lessons that are ingrained into your body, rather than relying purely on your own thoughts, Horii says, adding that there is a physicality to the process of writing.

WRITE ON THE FLY

What it takes to write a book is a single original idea combined with things that have already been written about it, Horii says. Many people self-destruct because they try to be original all over. All you need to do is to provide one new perspective, says Horii.

So, if you want to write about a historical figure, start writing and build momentum. The aim shouldn’t be to present the entirety of that person, but to highlight a single point that caught your attention, and to pursue that angle relentlessly. Collect data afterwards.

Self-expression through writing is possible, but that occurs only because writers can’t help but leave traces of their personal, almost physical traits in their written work, Horii says, adding: “It’s not so much self-expression but something that would come to the fore, even if you were to try to hide it[7].”

When he was writing a weekly magazine column, Horii says his aim was to write an enjoyable story, something that readers would find fun and exciting. The key is to write on the fly, Horii says. Latch on to thoughts that pop into your head and write about them. Don’t spend time mulling over what you plan to write, and don’t keep trying to hone your article once you’ve written it. “To write something that I could only write at that particular moment, just as I was writing—that was the important thing[8],” Horii says.

As I read Horii’s book, I found myself agreeing with many of the points he made and becoming fascinated by some of his other assertions. They both contain useful hints. Horii mentions the importance of writing immediately once inspiration strikes, and I’ve found that such a style of writing works best for me as well. The fresher the idea, the more momentum you build as you write. That can quickly snowball, and the fun and excitement you feel in those moments, you hope, will result in a story that other people may find entertaining.

[1] The book was displayed on a shelf outside a used bookstore, on sale for 100 yen, and I couldn’t resist buying. (That amounted to about 70 U.S. cents as of May 6, 2025, when the dollar was trading near 144 yen.)

[2] Horii, “Imasugu Kake, no Bunshoho,” p.55.

[3] I’ve learned this the hard way. My first instinct is to collect books and articles and to try to read as much as I can about a topic. That approach, though, has hardly ever led to any specific story angle.

[4] This point was drilled into me by my first boss, many years ago. You should always have your own guess and assumption as to why something is happening. Then go out and conduct interviews and reporting, collect facts and data to check whether your assumption is true.

[5] Don’t try to collect every piece of information on a topic, you’re aim isn’t to start a museum exhibit. If someone you know starts collecting information left and right to write a book about a historical figure from their local town, tell them to stop, Horii says. Thinking that you have to learn everything about a topic and write about that whole picture is foolhardy, he adds.

[6] Horii, p.54 「人は他人の意見なんか聞きたくない。聞きたいのは他人のお話だけである。」

[7] Horii, p.147.

[8] Horii, p.152.

コメントを残す