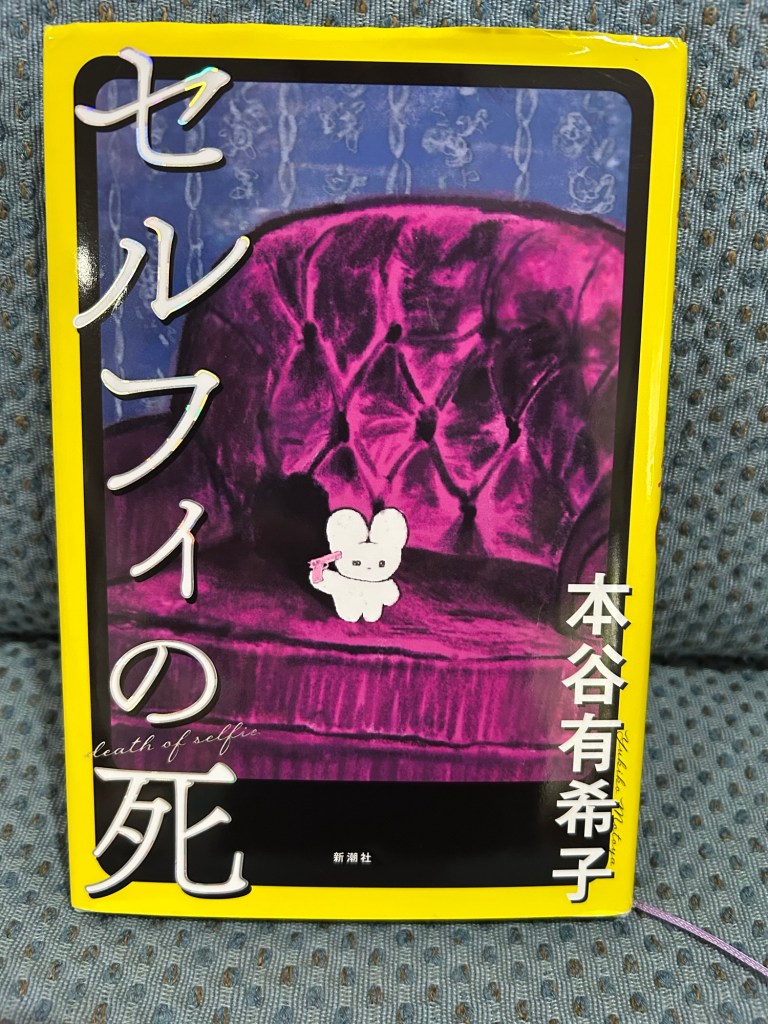

“Death of Selfie” is a strange book. The story begins with Mikuru heading to Nogizaka in central Tokyo to meet her friend Sora. Mikuru[1] is the type of person who is obsessed with the number of followers she has on social networking services (SNS), say Instagram or Facebook, or some other comparable platform.

Mikuru and Sora meet up at a cafe. It’s a popular place with a quiet atmosphere. Most customers look older than they are, and have the content, relaxed aura of people who are financially well-off and have a wealth of spare time.

Mikuru feels immediate disdain for a veteran store employee, a woman dressed in a maid-style uniform, who greets her after she enters the café. Mikuru is always looking for ways to get the upper hand in social interactions – “mount wo toru[2]” – and adopts a condescending attitude toward people she dislikes, including the café employee.

Once they get to their seats, Mikuru and Sora immediately start taking selfies. Even when other café-goers get annoyed and start shooting glances at them, they pretend not to notice and selfie their hearts out. When a young male store clerk offers to take a picture of the two, Mikuru becomes agitated, upset that a stranger had the gall to disrupt her routine. The female store employee jumps in to help her colleague, telling Mikuru and Sora to stop taking selfies as their obnoxious behavior is upsetting other customers.

Sea anemone-like tentacles that had popped out from the faces of Mikuru and Sora start to rot, and the two start pleading and begging, saying they can’t stay alive unless they take selfies. What in the world are they? Are Mikuru and Sora perhaps aliens from another planet who just appear to be human on the outside, like the aliens in “They Live,” a science fiction movie from the 1980s?

The book’s major themes are ego and the desire for recognition. The author tackles them through several short story-like chapters. In one episode, Mikuru meets an Instagrammer called Massu, to apologize for stealing a photo of a bird[3] from his Instagram page. Mikuru had altered the color and contrast and cropped his finger from the photo, and then posted it on her Instagram page, inviting Massu’s wrath. Mikuru had done this after she’d noticed that videos of cute-looking birds were trending on Instagram. The meeting quickly devolves into a mount position-taking contest between Massu and Mikuru which leaves Mikuru’s ego battered and bruised.

There is a number at the start of each episode that shows the number of followers Mikuru has on SNS. She remains unhappy, however, even as that number keeps increasing steadily.

Reading this book reminded me of a newspaper article I read recently. The article was a story[4] in the May 1 edition of the Asahi Shimbun, a major Japanese daily, titled “Doga de mitsuketa watashi no ‘shinjitsu’” (The “truth” that I found from watching videos.) It was about a group of demonstrators who had gathered in front of Japan’s Ministry of Finance, calling for it to be dismantled. To be sure, there’s nothing strange or unusual about people expressing their opposition to government policies. What was interesting, though, was that according to the article, there were people who took part in the demonstration because of videos they had seen on social networking services.

According to the Asahi Shimbun story, one person had come there to take videos of the demonstration and to post them on SNS sites, figuring such videos would attract lots of viewers and boost the income they gain from the videos. A YouTuber who posts videos about political topics was also there, although that person noted that interest in these anti-finance ministry demonstrations, and the boost to viewer numbers gained by posting videos about them didn’t last very long. While there was a boom earlier in 2025, interest seemed to have peaked out by March, the Asahi Shimbun quoted the 36-year-old male YouTuber as saying.

What should we take away from all this? Does this show that the number of people who are hell-bent on attracting viewers and followers, who crave recognition like Mikuru and Sora, are increasing in lockstep with the evolution of SNS?

As of May 2024, the number of people in Japan who watched YouTube per month totaled more than 73.7 million, a story in the Oct. 23, 2024, online edition of the Nihon Keizai Shimbun cited YouTube’s parent company Google’s Japan office as saying[5]. That amounts to some 68 percent of people in Japan who are 18 or above, according to Google’s Japan office.

To be sure, even well before the advent of SNS, there have been jobs and roles that stand to profit by gaining popularity, such as private television broadcasters, authors, and actors.

Still, in the past, in order to monetize popularity, one needed to have ties to broadcasting companies, book publishers, and film distributors. The evolution of SNS and creation of a system where people who upload videos can directly gain income if their content is popular, seems to have led to an ever more popular belief that attracting attention is more important than anything else, a disquieting development.

That being said, I’ve been writing a blog that features book reviews and other articles. The way the website is set up, even if readership numbers were to get a boost, that would not directly lead to any income. Even so, I pay close attention to the number of people who visit the site. I’m happy if there is even one visitor per day, and happier still if the number of visitors increases compared to the week before or a month ago.

Mikuru and Sora had seemed like aliens from another planet, but I’m similar, in the sense that I want my blog to be noticed. How should one cope with such a desire for recognition? The only solution may be to try to achieve a reasonable balance and to prevent that desire from spiraling out of control.

This book, “The Death of Selfie” is far from a light or relaxing read. It’s a stimulating piece of work, though, one that prompts you to think about current social trends and to face up to your own thinking and values.

[1] Mikuru seems to be a teenager or in her early 20s, but the author only hints at her age.

[2] The phrase means to “take a mount position” and is commonly used nowadays. I don’t recall it being used 25-30 years ago, in the early to mid-1990s. It seems to be a 21st century invention and has become increasingly popular over the past couple of decades.

[3] Buncho or java sparrow.

[4] 『動画で見つけた私の「真実」:似た主張次々 財務省解体デモへ』朝日新聞 2025年5月1日朝刊14版 22頁。“Doga de mitsuketa watashi no ‘shinjitsu,’” Asahi Shimbun online edition/14th version of the morning edition, May 1, 2025, page 22.

[5] 『YouTube国内月間視聴者7370万人 猫ミーム16億回再生』日本経済新聞オンライン版 2024年10月23日付。”YouTube’s monthly viewership in Japan at 73.7 million, cat meme viewed 1.6 billion times,” NIKKEI online edition, Oct. 23, 2024.

コメントを残す