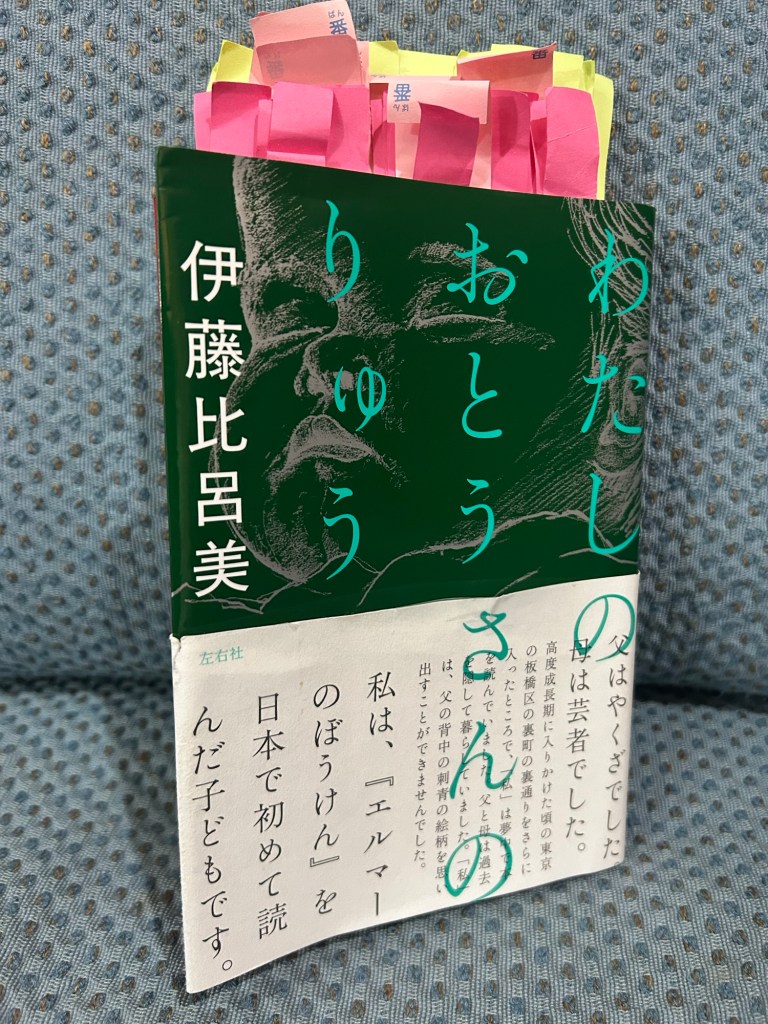

This book was recommended to me, and when I saw a photo of it, I was intrigued by the book’s title, its green cover, and the blurb, which begins with: “My father was a yakuza, and my mother was a geisha.” Is this perhaps some kind of adventure novel?

Eager to get my hands on the book, I looked for it at local bookstores and also on Amazon and online marketplace Mercari, but to no avail[1]. I finally bought a copy at a large bookstore in Kyoto.

Going back to the blurb, this is how it describes the setting: the backstreets of Tokyo during Japan’s post-World War Two era of high economic growth. It then ends with the following declaration: “I became the first child in Japan to read Elmer’s Adventure.” I wasn’t quite sure what to make of all of that.

As it turns out, this book, “Watashi no Otosan no Ryu” by Hiromi Ito, a poet and novelist who made her professional debut in 1978, is a collection of autobiographical essays in which the author reflects upon her relationships with her parents, both of whom have passed away, and their unique backgrounds. In the process, Ito shares vivid memories from her childhood and introduces a host of characters so unusual and visceral that they seem to belong in a work of fiction.

Ito starts her tale with a series of essays detailing her encounter with the popular children’s book “My Father’s Dragon,” which was written by Ruth Stiles Gannett and published in the United States in 1948. In Japan, the children’s novel was published in 1963 under the title “Elmer no Boken.[2]”

That year, Ito says her father, who at the time ran a small printing company in Itabashi Ward in Tokyo, read her a galley proof of the Japanese version of the book. Her father would lie down on a rattan lounger on the engawa of their house, reading out loud to Ito as she sat nearby. That is how, Ito says, she became the first child in Japan to read “Elmer no Boken.”

Ito’s relationship with the book continued into adulthood.

After she moved to the United States with her children, Ito says she came across the book in a California bookstore where she discovered, to her surprise, that its original title was “My Father’s Dragon” and not “Elmer’s Adventure,” which is what she had come to expect based on the title of the Japanese version of the book. She bought a copy of the U.S. original for her children but stopped short of reading it.

Years later, when Ito and her family were still living in California and the youngest of her three children was about five or six, a friend of one of her children came over to play. The two children were behaving so quietly that Ito says she took a peek, curious to see what they were up to. It turns out that they were reading, and Ito spotted her daughter’s friend cradling the book “My Father’s Dragon.” She later gave a copy of the book to her daughter’s friend as a birthday present, and Ito would go on to do the same whenever one of her children was invited to a birthday party.

Still, it was only some years later, after Ito had returned to Japan and ordered an e-book version[3] of “My Father’s Dragon,” that she had a chance to read the original English text.

It was then that she realized that the nuances of the U.S. and Japanese versions of the book differed.

For one thing, Ito noticed that “Elmer,” the name of the protagonist, hardly ever appears in the original English text, which refers to him mostly as “my father”.

For another, while the Japanese translation used the male pronoun “boku” to describe the protagonist’s child, who narrates the tale, Ito saw that there was nothing in the original English text that identifies the narrator as being a boy. (To be sure, the choice here in Japanese would be to use either the masculine pronoun “boku” or the feminine “watashi.” There is no gender-neutral way to translate the word “my” to Japanese, and Ito makes clear that she isn’t dissatisfied with the way the text was translated.)

The book continues in this vein for the first several essays, with Ito sharing not only her memories of U.S. and British children’s books and impressions of the Japanese translations and how their nuances compare to the original texts, but also providing her interpretations of the stories, and highlighting the messages that she took away from reading them.

In an essay later in the book regarding a collection of classical foreign literature for children that was published in Japan, Ito says she saw a common thread running through the stories selected by the book publisher, editors and translators who had worked on the collection. “Adults at the time all lived through the war and were living in its aftermath.” Ito says. The stories all dealt with journeys of some kind as if that was the books’ purpose and the message the adults wanted to impart, Ito says, in the hope that young readers would gain a measure of freedom from the family.

Throughout the book, Ito delves into her parents’ background, starting with her father and recalling how he always seemed to be surrounded by younger men, regardless of whether he was running his printing business, visiting his sister in Choshi, a city on Japan’s eastern coast, where tattooed men who knew him from his days as a Yakuza would constantly drop by to say hello, or even in old photographs taken during World War Two, when he served in the Imperial Japanese Army as a flight instructor for the Tokkotai, according to Ito.

Eager to learn more details about her father’s wartime experiences, Ito obtained from municipal authorities in Tokyo a document listing her father’s military service and where he was stationed at. According to Ito, the record showed that her father, after graduating from college, received training at an army flight school in Kumagaya city, about 60 km north of Tokyo. He later became a flight instructor, and the document showed that he arrived in Manchuria in April 1945.

Ito had heard from her father that he had trained 15- and 16-year-old boys to become pilots. Ito’s father said that he had also volunteered to become a Tokkotai pilot himself, but the war ended before he went on a mission. When the war ended, he was able to fly back from Manchuria with other military personnel even as many other Japanese were left behind, a development for which Ito’s father was critical of the military.

Ito also conducted research into her father’s post-war experience as a member of a Yakuza family and came across information that corroborated things she had heard from her parents that hinted at acts of violence committed by her father. The research led her to a 1949 newspaper article about an incident involving Yakuza in Choshi that mentioned Ito’s father by name. During her research, she became acquainted with a non-fiction writer who helped with Ito’s research into her father’s past.

Compared to her father, Ito says she is less emotionally invested in her mother. Ito recalls that when she was a child, her mother would often slap her when she became annoyed. Ito says that when she was younger, she felt only a sense of rebellion against her mother. “Or maybe I didn’t even rebel. I probably didn’t even consider her to be someone worth rebelling against,” Ito says.

Ito adds though that she also has memories of her mother being at her side when Ito was sick with fever as a child. Her mother was also at her side when Ito went through a personal crisis soon after she graduated from college.

Ultimately, Ito comes to terms with her relationship with her mother and the life that her mother led, ending her fascinating, visceral and engrossing tale on an uplifting note.

I was captivated by this book from the start, quickly drawn in by the author’s description of childhood memories about her father’s printing business, and by the way in which she shares her experience with children’s books to highlight the trickiness inherent in translating words, the way nuances can be changed or may even need to be added, when trying to explain words and concepts that are common in one language, in another language to which such notions are foreign.

The author’s research into the personal histories of her parents was also intriguing, including her explanation of how she gathered information pertaining to her father’s military service and the way she melded them with things her parents had told her, to try to deduce and to piece together a fuller picture of their experiences.

This book reads like an account of a long journey or a quest, an experience that is at times arduous and excruciating but almost always compelling, and in that sense, perhaps hearkens back to books such as “My Father’s Dragon” not just in title, but in content as well.

[1] The book’s first printing was published in October 2025. Back in late December, the Amazon app showed that the book would only be shipped around late January, and no one was selling it on Mercari.

[2] A rough translation of the title would be something like “Adventures of Elmer” or “Elmer’s Adventure.” The book was translated by Shigeo Watanabe, a prolific translator of children’s books. He was born in 1928 and passed away in 2006. (“Watashi no Otosan no Ryu,” Hiromi Ito, 17.) Books translated by Watanabe include “Harry the Dirty Dog” by Gene Zion and “Pretzel” by Margaret and H.A. Rey, according to Fukuinkan Shoten Publishers, Inc’s website.

[3] Ito says she purchased e-book versions of all 3 books in the “Elmer” series. Ito, 16.

コメントを残す