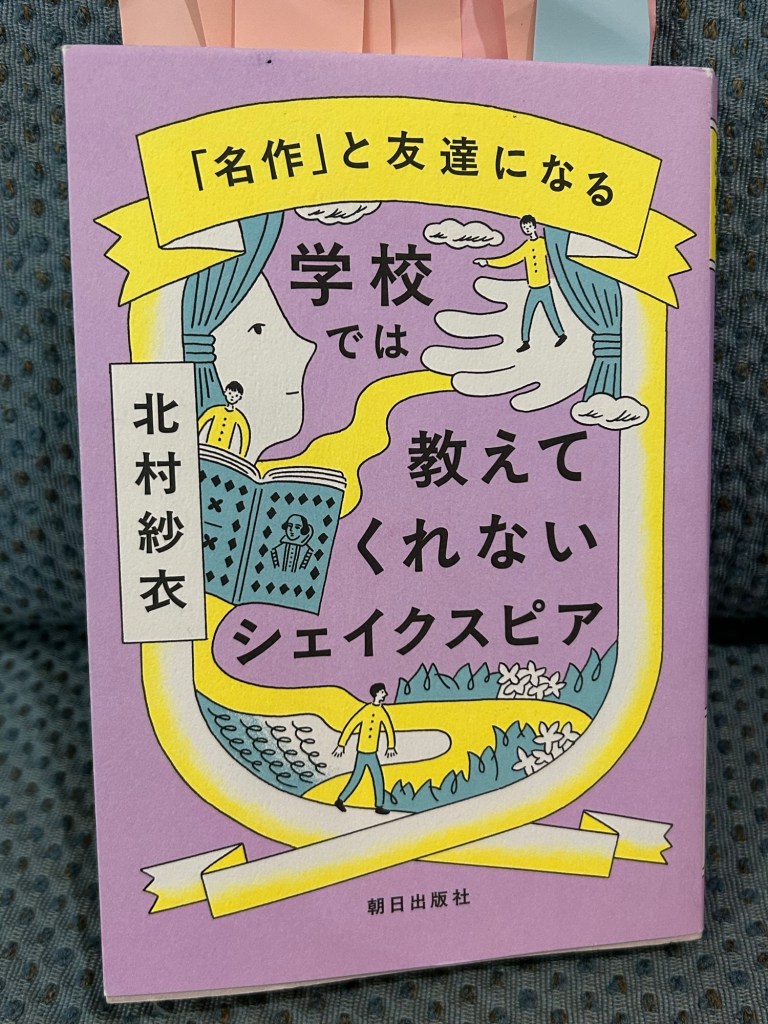

『「名作」と友達になる 学校では教えてくれないシェイクスピア』 北村紗衣 朝日出版社 2025年9月2日初版第1発行

I’ve always wanted to read and learn more about William Shakespeare ever since a professor[1] at a Japanese university said during class more than 30 years ago: If you want to gain a deep understanding of English, you should read the Bible and Shakespeare.

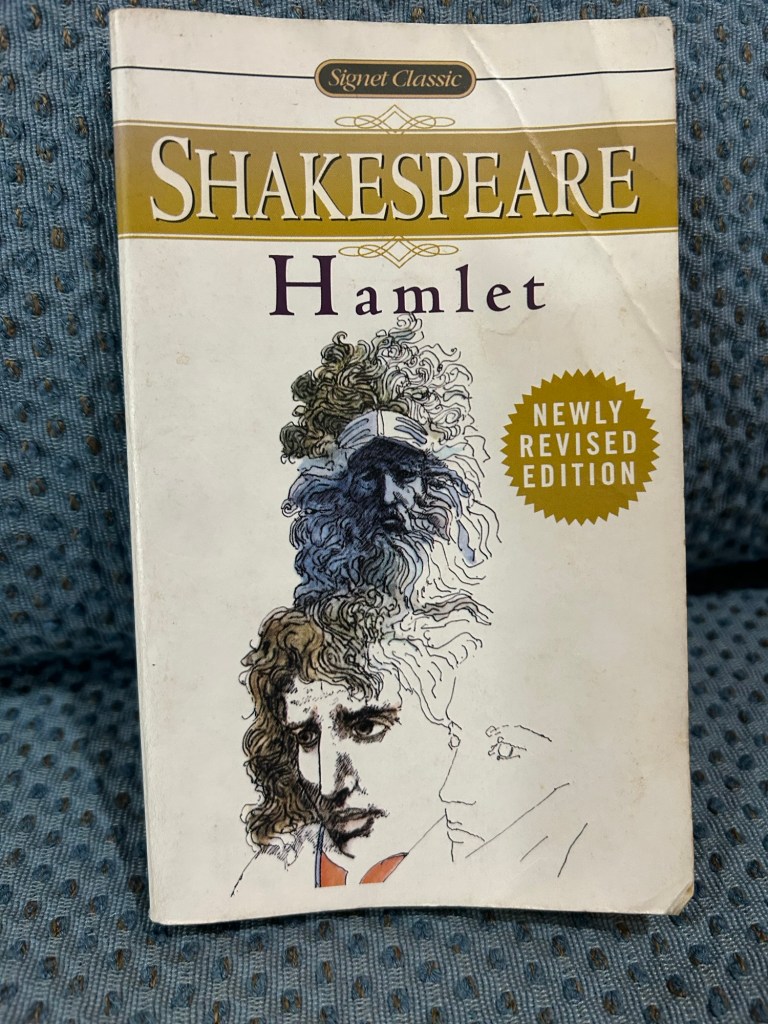

I never got around to reading Shakespeare while I was in college. But the advice stuck with me, and I eventually tried reading Hamlet. To my disappointment, I could hardly make heads or tails of what was going on.

When I recounted my experience to a couple of native English speakers[2] last year, they laughed. I mean, they cracked up and were laughing so hard, they seemed ready to roll on the floor. I was non-plussed by their reaction.

After they recovered, the gist of what they said was that Shakespeare’s writing isn’t easy to understand, even for native speakers of English. You should watch his plays instead of reading them, they said[3].

So, when I saw this book, Becoming Friends with “Masterpieces”: Shakespeare — What They Don’t Teach You in School at a local bookstore, I couldn’t resist. It seemed like a book that would provide a good introduction and help me get into Shakespeare.

The author, Sae Kitamura, is a professor of British and American Studies at Musashi University in Tokyo. She studied culture and representation at the University of Tokyo and received her PhD from King’s College London. She specializes in Shakespeare studies, history of the performing arts and feminist literary criticism, watches about 100 plays and 100 movies a year and is a Wikipedian to boot.

Her previously published works include Women Who Enjoyed Shakespeare’s Plays (Shakespeare Geki wo Tanoshinda Joseitachi), which was based on her doctoral thesis and examined how female audiences in the late 16th century to late 18th century[4] reacted to Shakespeare’s plays. She has also published a collection of her reviews and a book on literary criticism, among other works.

Kitamura’s latest book is based on a series of lectures that she gave in July to September 2023 to a small group of students from two all-boys high schools in Tokyo. The lectures were aimed at teaching students how to take a critical approach to enjoy Shakespeare’s plays, while considering the historical background and issues related to gender and sexuality.

The book begins by covering details about Shakespeare’s life starting with the basics: he was born in 1564 and died in 1616. Kitamura reckons that probably all English literature departments in Japan teach students to memorize those years using the following Japanese mnemonic phrase: hitogoroshi no hanashi wo iroiro.

Kitamura mentions a couple of misconceptions about Shakespeare that seem common in Japan. She says she has often been asked whether Shakespeare was from the Middle Ages and whether he was a novelist. He was actually from the Early Modern period and didn’t write any novels.

Kitamura also highlights the prose and rhythms used in Shakespeare’s works. The plays use Early Modern English[5] and employ a cadence called the iambic pentameter, in which a line of verse is made up of five pairs of two syllables each, with the stress always falling on the second syllable.[6] The poetic rhythm was commonly used in English poems and plays from the Renaissance Era.

Toward the middle of the lecture series, Kitamura showed the students modern movie adaptations of a couple of Shakespeare’s plays, namely the 1996 film “William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet” directed by Baz Luhrmann, and the 2001 movie “O” directed by Tim Blake Nelson.[7] Both films used modern-day settings, with the story of “O” set in a U.S. high school in the year 2000.

Such adaptations underscore the influence of Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, a 1961 book written by Polish scholar Jan Kott, who Kitamura highlights in one of her lectures. Kott called for Shakespeare’s plays to be staged as if they had been written for modern-day audiences, a notion that has since become widespread.

Toward the end of the lecture series, Kitamura turns her attention to the practice of literary criticism, seeking to impart upon students the key elements.

So, what goes into writing a good piece of literary criticism?

Kitamura says all analyses and interpretations of a play should be based on evidence, and consistent with the facts as they are presented in the play. Specific examples, such as lines spoken by characters, props, imagery etc. should be cited as the rationale for any interpretation or analysis, whether it be praise or criticism.

In any piece of criticism, the plot of the play being critiqued should be summarized accurately and the key concept and message of the play should be highlighted. Writers may choose to refrain from mentioning some plot details to avoid spoilers, but their plot summaries should not mislead readers. (On the issue of spoilers, Kitamura says it is ok to have them in literary criticism, since critiquing a work properly often requires the writer to refer to the story’s conclusion.)

Ideally, plot summaries would be kept short, to a few lines. The writer should then start analyzing the work while weaving in additional descriptions about it, Kitamura says.

The writer should focus on a specific angle when writing criticism. They could hone in on details that appear repeatedly in a play, perhaps the prevalence of water, or some other prominently featured element and analyze their significance.

When in doubt, Kitamura suggests starting with basic information about the work being critiqued such as the name of the author or director, when the play, book or movie came out, etc. After that, present the angle and start analyzing.

Such advice contrasts with many of the book reviews I’ve written so far, which have consisted of long plot summaries and a few personal impressions added at the end, as I am doing now. To write more compelling reviews and criticism, I would like to work on incorporating the advice given in this book.

That is, try to keep plot summaries short and then present the angle while weaving in additional descriptions of the book. This will no doubt be a long-term project.

Reading this book also made me realize just how little I know about William Shakespeare and his plays. Maybe it’s time I went and watched the movies cited in this book and took a stab at reading the original plays. Perhaps then, I’ll learn to appreciate them for the classical works that they are, rather than only remembering them as the topic of a random conversation, which left me perplexed and people nearby convulsing in laughter.

[1] The professor is from the U.S. and his suggestion still sounds very reasonable.

[2] A couple of people, also from the U.S.

[3] To be sure, I once watched an English-language performance of “Othello” but that proved just as difficult to understand.

When I asked for advice on a good classic to read, one suggestion was to read “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, since it contains lots of realistic sounding conversations.

[4] The research covered the period up to 1769, the year of the Shakespeare jubilee. Kitamura explains in her book that this was the first major fan festival type of event that was held for Shakespeare.

[5] Old English was used in England until the 11th century, Middle English came into use after the Norman Conquest in 1066 and Early Modern English from around the 16th century to the mid-17th century. Kitamura, 128-129.

[6] In Japanese, iambic pentameter is called jakukyogohokaku. (弱強五歩格)Kitamura, 136.

[7] The book mentions that this movie adaption of “Othello” contains shocking depictions of violence and sex, and that it is a very dark film.

コメントを残す